I’ve written in the past about not voting. I was writing in the midst of President Obama’s second term, after five years of watching Hope and Change fail to live up to my expectations. Where was the closure of Guantanamo? Where was the single-payer healthcare law? Where was the era of peace promised by resets, pivots and ending wars? I was tired of a corrupt system that limited political choice between two parties that were fundamentally the same, save for some shades of difference on social issues. The answer seemed to be to withdraw from the entire process. I couldn’t change the system, but I could at least withdraw my tacit support from the system. I could end my complicity.

In the years since that blog, I’ve realized that I was wrong to write that. The realization didn’t come in a blinding Road to Damascus moment. It came little by little, over conversations with friends and watching the way that politics actually plays out in reality, not the rhetoric of a campaign. I saw the improvements that even an “unacceptable” compromise like the Affordable Care Act could bring to people’s lives. I watched friends and family get involved in the process, and talked to them about how easy it is to hurl slogans and platitudes, but how hard it is to actually be the person to make decisions that impact individuals.

But mostly, I’ve watched hundreds of thousands of people die in the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia since the invasion of Iraq. Historians will be sorting out the geopolitical importance of the September 11th, 2001 terrorist attacks for generations, but there are two views we can take of it as of today. One is the narrow view, where the response to September 11th included the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. In that case, more than 26,000 Afghan civilians have been killed since 2001, and more than 161,000 Iraqi civilians have been killed as a direct result of both wars.

The other is a more expansive view, where the invasion of Iraq destabilized the entire region, strengthened Al-Qaeda for a time, led to the Arab Spring and the Syrian Civil War, and the creation of the Islamic State. If we count these developments as outgrowths from the foreign policy blunders of the United States (as we rightly should), then we have to add at least 470,000 Syrian deaths to the above total.

The American government which started the wars in the Middle East was elected by 537 votes in the state of Florida during the 2000 election. Much has been written about whether or not Ralph Nader spoiled the election by drawing away left-leaning voters from Al Gore. While Nader vehemently denies this, others have concluded that Nader (along with other left-leaning candidates) did in fact cost Gore the victory in Florida, and the leadership of the American government. Instead, George W. Bush became president, and the rest is history.

There’s an important rhetorical reason for blaming the Iraq War and the subsequent disasters in the Middle East on the American government instead of the Bush administration. Calling it the Bush administration allows us to distance ourselves from the decisions that were made, as if to say, “I didn’t vote for him, so I’m not responsible.” Yet we are responsible, regardless of how we vote. We live in a republic, where elected officials speak and act in our interests and our name. We peacefully consented to the transfer of power from the Clinton administration to the Bush administration. There were protests and disagreement with the decision to invade Iraq, yet a majority of Americans supported the decision at the time. The government that we chose, both by voting for George W. Bush AND by not voting for Al Gore, acted, and more than half a million people have died because of it.

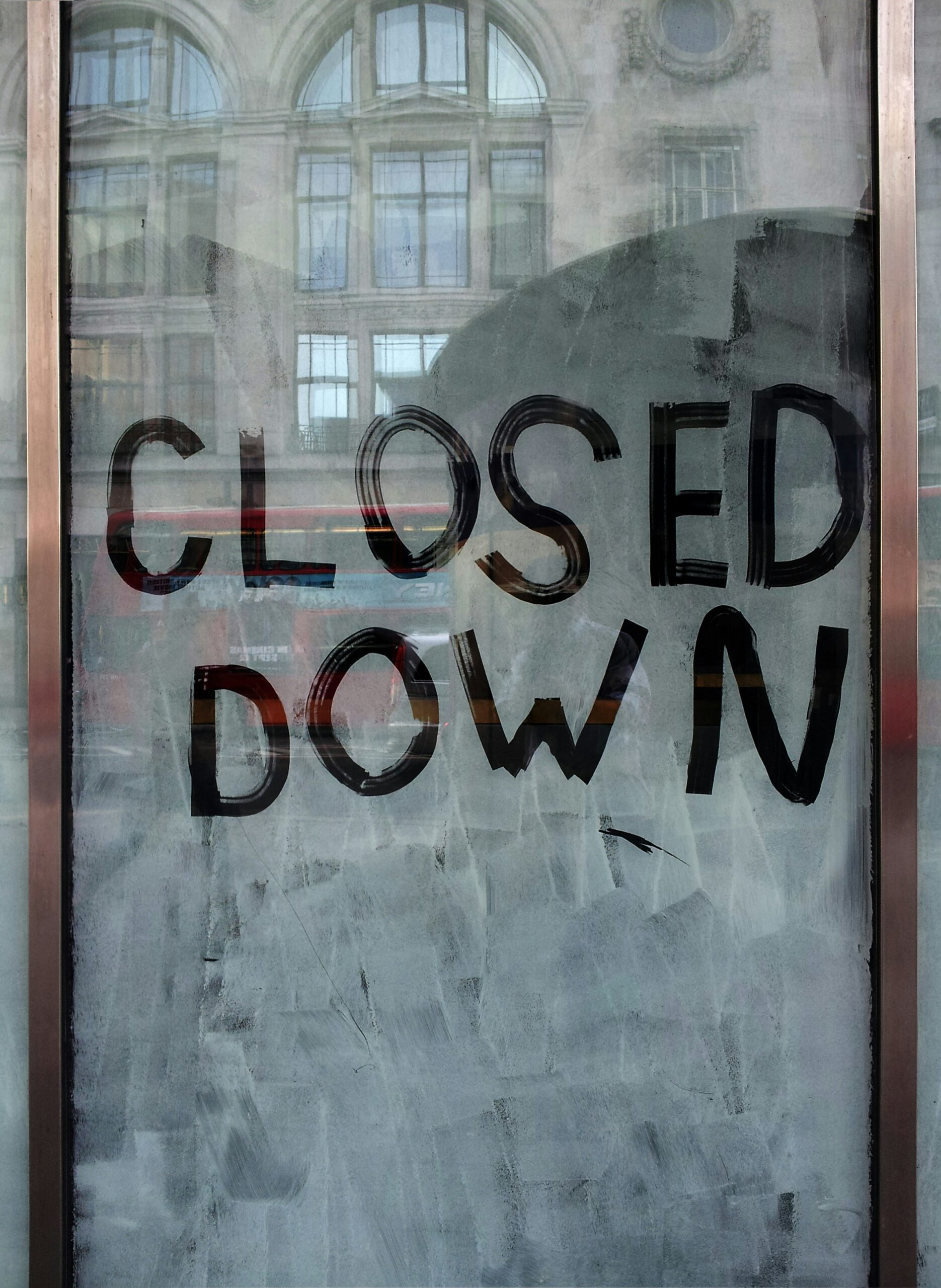

The global aftermath of the decisions our government made in 2003 has made another lesson all too clear: It’s not enough to vote. We also have a responsibility to vote wisely, and to consider the effect that our vote has on the rest of the world. The old adage may be that all politics is local, but as Americans, our local decisions have global repercussions. Our nation has the power to project military, economic and political power anywhere in the globe in a matter of hours. When our politicians and policymakers make decisions, the result is that people somewhere on earth may die. That’s an enormous responsibility, but it’s too often taken lightly by us. We throw around the phrase “My vote doesn’t matter” with a level of glibness that ignores the potential consequences for people who are not us. We only need look at the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union as evidence of what can happen when people don’t take the impact their vote will have on others seriously. This not only extends to the decision to vote itself, but also who we choose to vote for.

As Otto von Bismark put it, “Politics is the art of the possible.” In the political system which currently exists in the United States, it is not possible for Dr. Jill Stein to win the presidency. Third party candidates do not have the national infrastructure, money or exposure to have a legitimate chance at victory. Even Bernie Sanders, a political independent for his entire career, realized this and chose to run as a Democrat. Perhaps that will change someday, but it won’t between now and November. What third party candidates have the power to do today is to draw votes away from the two major parties and affect the outcome. That happened in 2000, and it’s possible again this year.

All of this is to say that any registered voter who does not want to see Donald Trump as the leader of our government has a responsibility to not only vote this fall, but to vote for Hillary Clinton. You don’t have to like her. You don’t have to agree with her. You don’t have to feel good about casting the vote. Elections are about more than how you feel though. Progressives who supported Bernie Sanders (or Martin O’Malley) often point to Clinton’s super-predator statement, or that she was part of the conservative shift of the Democratic party in the 1990’s that her husband led, or that she is hawkish in her approach to foreign policy, or that she has supported the Honduran coup in 2009. Let’s concede all of those as true and valid critiques of Clinton. The question remains: Would President Donald Trump be better for anyone, anywhere in the world?

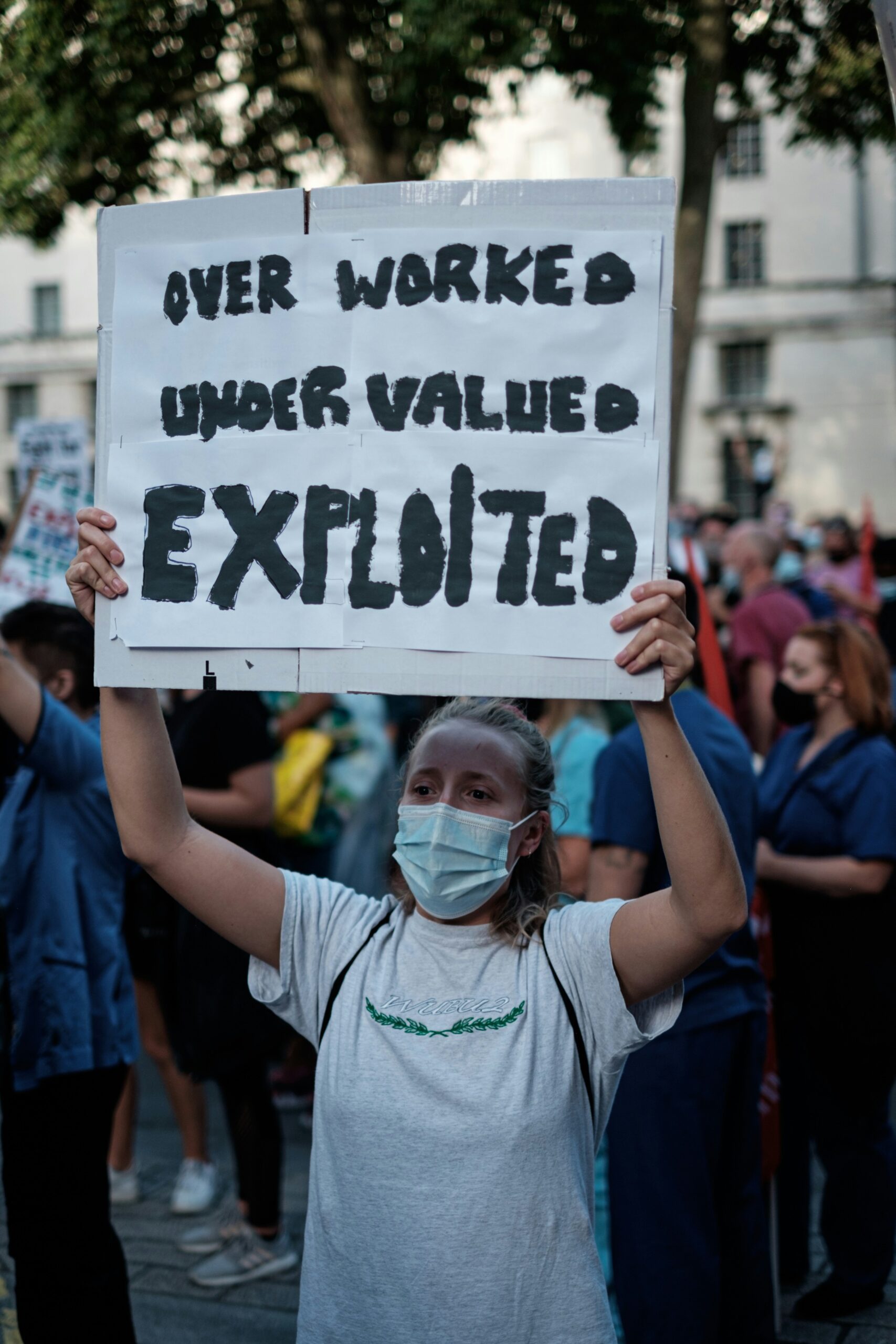

Another argument some use to justify not voting for Clinton is that they refuse to choose between two undesirable candidates in an undesirable system. Jerry Garcia’s quote, “Choosing the lesser of two evils is still choosing evil” usually accompanies this argument. These same people eat food picked by undocumented migrant workers, wear clothing made by child laborers, and drive cars which contribute to climate change. We all commit evil in this world simply by existing and going about our day-to-day lives. To paraphrase Spiderman, we must accept the great responsibility that comes with our power as American citizens, especially in a season of imperfect choices. There are never perfect choices, yet we still must choose. We owe it to too many people in too many places to choose poorly.